Walk into Robbins Library and you’ll be graced by many beautiful pieces of art along our walls. We have prints from Jack Coughlin of numerous authors, including Toni Morrison, Herman Melville and Edgar Allen Poe. There’s a large print of Lord Byron by Rembrandt Peale right next to our supervisor’s office. There are also numerous facsimiles of medieval manuscripts and art. But our largest pieces, one above our mighty director’s door and one directly on the wall opposite of it past the shelves, are from American surrealist painter Honoré Desmond Sharrer.

Sharrer, aligning herself with the magical realist and surrealist traditions, honed her aesthetics through formal education at the Yale University School of Art and the California School of Fine Arts. While some of her contemporaries, such as Robert Motherwell, Jackson Pollock, and Mark Rothko, focused on what we recognize today as abstract expressionism, her focus on the human figure and wit distinguished her from the aesthetics that marked this era of art in the United States.

Tribute to the American Working People, which is now part of the permanent collection at the Smithsonian, is one of her largest and most recognizable works. She was also featured in the New York Museum of Modern Art’s 1948 “Fourteen Americans” exhibit alongside some of the artists mentioned above. Late in her life Sharrer commented that “[ordinary] matters are the largest category of subjects in my painting; then, the next largest subjects are myths, including religious subjects (whether in jest or earnest), and then nursery rhymes.”

Of our large-scale works from her, we have "The Judgment of Paris," oil on canvas, which depicts three nudes with strange dispositions (one balancing herself on her left foot and right middle finger) dancing in front of a clearly uncomfortable clothed man. We’re also proud to have her St. Jerome, which depicts a withered masculine body in a moment of contemplation. Through these pieces we see a lot that defines Sharrer’s work, with its scale, detailed figures, impressive balancing of greyscale alongside heavily saturated colors, and a sense of humor.

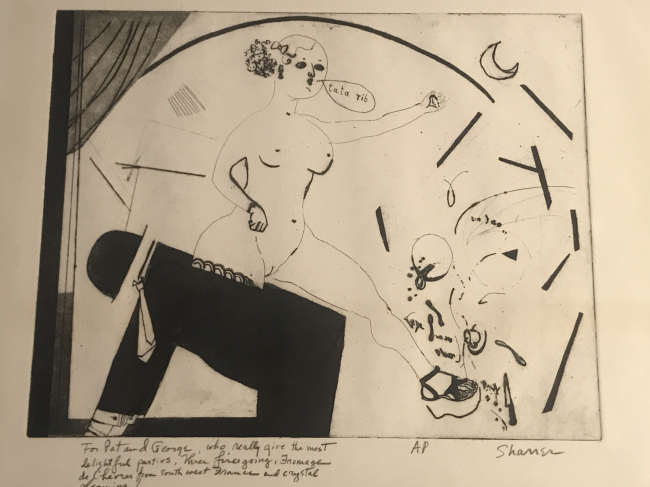

While these may be the largest of her pieces here at Robbins Library, we have one little piece, hanging to the left of the director’s door. The piece stands in stark opposition to our other Sharrer pieces, as it is a small piece, roughly 13” by 11”, and lacks color with solid, black geometric objects, negative whites, and small accenting patches of gray. Despite these differences, we’re graced by some of same elements of much of Sharrer’s work, such as the pale nude, surrealist depictions of objects, and a sense of humor that is almost always conveyed in her work through facial expressions and scene setting.

The scene depicted in this piece is a beautifully empowering take on the second creation of Eve where she is drawn from Adam’s rib. This scene is described in Genesis 2:21-25:

[21] So the Lord God caused a deep sleep to fall upon the man, and while he slept took one of his ribs and closed up its place with flesh. [22] And the rib that the Lord God had taken from the man he made into a woman and brought her to the man. [23] Then the man said, “This at last is bone of my bones and flesh of my flesh; she shall be called Woman, because she was taken out of Man.”

Typically, visual depictions of this scene have the Judeo-Christian god, or one of his angels, pulling a loving, longing Eve by her shoulders, arms, or wrists from a sleeping Adam’s rib as he rests his head on his arm. Sharrer puts a much needed spin on this biblical moment through her piece. In this case, we have most of the key elements. We have an Eve, bursting from the back along the ribs, of an Adam. But our Eve isn’t pulled out by god or an angel; rather, she almost seems to burst out of Adam on her own and reaches for a moon in the sky as she does. She is curvaceous, nude except for a garter belt around her right thigh, and her hair and makeup are done in a style reminiscent of a 1920s flapper. And even while she’s still thigh-deep in Adam’s back, we see her other leg, tipped with a platform sandal with ankle strap, stretched out and ready for her first step.

The Adam, in this case, isn’t some six-pack hunk like earlier depictions, but is nothing more than a hollow, geometrically oriented suit, tie, shirt and hat. And better yet he’s not lying back, restful, but rather hunched over on all fours. This whole scene trembles with surprise: this wasn’t a moment crafted by a masculine god meticulously planning the next piece of property for his finest creation, but a femme presence bursting from confines into a free world.

In front of her, a scene of sweet chaos. During her arrival, it seems like she’s knocked over a table, with cups and silverware included, and it dissipates into an abstract mess of curved lines flying away from her. In many ways, the icing on the cake, so to speak, of this painting is the world bubble that flies from her lips in this scene, and the title of the piece: ta ta rib.