As I discussed in my previous blog post, medievalist Margaret Schlauch abandoned her tenured position at New York University and fled to Soviet-controlled Poland in January 1951 under increasing scrutiny from the McCarthy-esque Senate Subcommittee on Internal Security (SSIS) for her lifelong commitment to anti-fascist activities and communist sympathies. Unable to return to the United States forward decades, Schlauch corresponded regularly with Rossell Hope Robbins, his wife Helen Ann Mins Robbins, and her brother Henry Felix Mins, Jr. [1] The letters—now housed in The Robbins Library along with other relevant materials, including Henry’s unpublished writings and newspaper clippings related to the hearings—offer unparalleled insight into the life of a politically active academic.

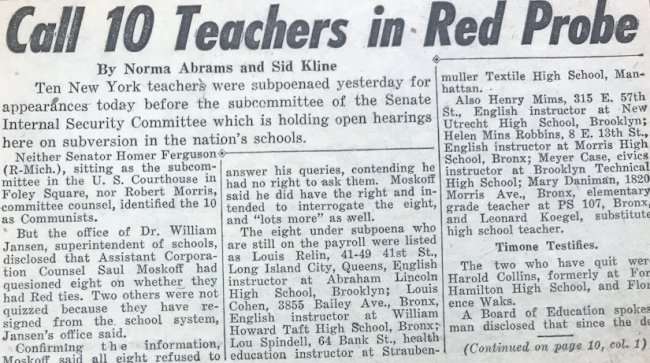

This is particularly true of those letters from late 1952 and 1953, which recount the aftermath of Bella Dodd’s SSIS testimony in September 1952 that hundreds of communists had infiltrated schools in and around New York City. Helen Ann and Henry were among the first teachers named by Dodd. Newspaper reports, such as this article from the 10 September edition of the New York Daily News, names the teachers who have been subpoenaed and ominously includes their home addresses and the schools at which they worked:

Henry did eventually have to testify before Sen. Patrick McCarran (D.–NV), Sen. Homer Ferguson (R.– MI), and lawyer Robert Morris—the three primary SSIS “inquisitors,” as he will eventually describenb them. A number of Henry’s unpublished writings relate to this hearing in one way or another. In one untitled document, Henry succinctly recounts his memory of his testimony, and his depiction of the committee’s tone is fascinatingly divergent from that recorded in the official record, Subversive Influence in the Educational Process. [2]

One of the most interesting documents in our collection, however, is Henry’s unpublished short story entitled “Nevada to Livingston Street.” Here, he minces no words in his analysis of the psychological and judicial violence the SSIS hearings, conducted in an ironically unassuming bureaucratic building, actually achieved:

This is the Federal Court building, a grey tower [with] a sort of [pyramid] on top. The corridors are of gloomy stone, and the courtrooms are panelled in walnut in bankers’ style, and here among other activities the Constitution is murdered, daily in many divisions and two or three times a week in another. In some rooms people are tried for their opinions; in another, they do not even get a trial. The apparatus for firing teachers operates automatically. […] The inquisitors want to get on the record the answer to the questions as to political affiliation, past and present. After that the sky is the limit. [...] What the committee does is a standardized routine, and has a sort of macabre logic of its own. In this rehearsal they want to test out the victim to [see what] will sound good in the public hearings and what lines of questioning they had better drop. They hope too (but with little success) to come upon someone who will show signs of weakening; then they will work over that man in other executive sessions, suitably spaced to produce the maximum of psychological disturbance. They are in no hurry to throw such a specimen to the lions; they have him where they want him, and he might name names if they can press hard in the right spots.

Helen Ann, in contrast, evaded the subpoena and entered early retirement, claiming that physical disability (arthritis) prevented her from teaching any longer. The experience must have been deeply trying for all involved, at home and abroad.

In this letter dated 25 September 1952, Schlauch responds to Dodd’s “havoc-wreaking,” which she learned about from a New York Times article. The article to which she refers is likely Charles Grutzner’s “1,500 U. S. Teachers Red, Dr. Dodd Says” (9 Sept. 1952). Here, Grutzner quotes an anonymous Teachers’ Union representative who calls Bella Dodd a “false witness,” dismisses her claims as nothing more than the usual slander, and suggests that she reread Matthew 27:3–5:

When Judas, his betrayer, saw that Jesus was condemned, he repented and brought back the thirty pieces of silver to the chief priests and the elders. He said, “I have sinned by betraying innocent blood.” But they said, “What is that to us? See to it yourself.” Throwing down the pieces of silver in the temple, he departed; and he went and hanged himself.

She tries to recall early “signs of corruption” in Dodd:

Years ago I recall [that there were] two warnings about her inner weakness which I brushed aside at the time. One came from a person whom Helen will recall by the nickname of The Queen, who said “careerist” at the very start—seemingly then, most unfairly. And the other—a statement from my own mother which I also rejected then, to the effect that we might one day regret trusting her [Bella] too much. Mother detected a core of egoism which I couldn’t see. But my sister now recalls that Bella once said, quite frankly, that she had coolly calculated which side would succeed, the fascist or the other, and decided that success would crown the latter—so she chose it. And she quite frankly expected to the [...] ALP’s [American Labor Party’s] first governor, she said, Well, it’s a heartbreaking story by any light, & hindsight makes it no less so. I never worked at all closely with Bella—but many who did truly loved her, I know. She had great quantities of magnetism and warmth (some of it, I did sense, of a quite animal character). [...] Her present performance must be causing untold damage—emotional as well as other. Dragging in divinity à la Bentley et al. is the most sickening part!

Taming her visceral “disgust at this newest vilification of religion,” Schlauch then offers the following poetic consolation as a kind of “counterirritant, to fight down a physical sickness at the whole miserable treachery”:

Now Bella Dodd

Is serving God

By turning state informer;

If He exists

She’s on His lists

For a place than this—much warmer!

Personal tragedies followed close on the heels of these collective political trials.

In this letter dated 14 February 1953, Schlauch recounts her response to the “not entirely unexpected” news of her father’s death. Because both she and her other brother Leonard now reside in Poland, she also worries about the health of her other brother William, who “[is] quite alone now, and latterly not feeling well himself.” He seems to have suffered from a heart condition that had mostly gone into remission but still prevented him from living independently. With these thoughts, the reality of her exile sinks in: “Where once there was family there won’t be anything left—a strange feeling. These are the days when I wish intensely it were possible to get back for a visit. I hated to think of William having to go through the readjustment, the legal settlements and the sorrowful formalities all by himself….”

Within two months, William too has died “suddenly but quietly—without any preceding period of suffering.” In this letter to Helen Ann, dated 27 April 1953, Schlauch seems remarkably subdued, quickly shifting her focus almost exclusively to the logistics of the situation:

"This was not unexpected; we knew he was failing; but the news was a real blow coming to us so soon after my father’s death. Now there’s no immediate family left over yonder. The estate is being settled in the absence of the heirs (Helen and me), [...] and this means that more than normal will have to go for lawyers’ fees. Not that we care very much. That side of the matter seems rather unreal to us living as we do here in a simpler, more austere and also more egalitarian and cooperative society. There is one factor that would make us want to keep the house instead of sell it: that is, if Emanuel & family would like to move in and run it for us. You see, William [...] had arranged to have them move in this summer, when the tenants upstairs were supposed ideal for William—congenial people to look after him, to take care of the place, and to enjoy it (it’s quite nice)—so far as we were concerned, rent-free in consideration of those services. If they’re still interested we’d still like to have them there."

Yet, Schlauch’s sympathy for the physical and emotional suffering that Helen Ann has been experiencing as a result of the SSIS investigations seems as much a personal insight as a general commentary on life:

"I know of the lads from S&S [Science & Society] chiefly because Henry has turned into a devoted correspondent, bless him—the others don’t write. Outside of the magazine and yourself I know little about the doings of victims—merely the fact that they have been thrown out. In your case I can imagine that there has been a kind of blessing in disguise in the situation. I’m not at all surprised that your arthritis is better since you are not subjected to the terrible pressures of teaching in a huge system which must have become more and more exacting in the recent years. I’ve long since been convinced that nerves are very tricky things and do have complicated hidden influences upon many aspects of our lives—even the lives of militant rationalists. Why shouldn’t we be more prone to aches and pains when we’re being harassed in spirit?"

The frankness of their exchanges throughout the whole ordeal is remarkable given the circumstances. In a letter dated 21 April 1951, Schlauch admits that it is common practice for the Polish and/or American governments to read citizens’ mail:

"Most of my friends appear to be rather more fatalistic about communications back and forth. They assume that a certain number are opened and photographed (filed away, I suppose, and read later if occasion warrants); but my guess is that this is done by the method of sampling. Such are the indications anyway. And so we write on both sides with an awareness of this, but don’t let it bother us too much. I don’t think that my doings can be of very general interest, after all."

Additionally, a rare letter from Rossell, dated 8 February 1955, states that “it is almost amusing, as well as irritating, to see how all of [his] foreign mail […] has been opened and often not resealed or else badly done with the new glue looking very yellow.” This suggests that the U.S. government found the “doings” of at least one of these comrades to be of great interest. Given the nature of the SSIS’s investigation, this same oversight must certainly have obtained during the latter months of 1953.

Notes

[1] Schlauch had strong connections to all three. A medievalist like herself, Rossell and she regularly discuss manuscripts, philological questions, recent publications in the field, etc. She and Helen Ann, also a radical, were both active members of the American Association of University Women (AAUW) and the Teachers' Union, and they had both taught in the public school systen. And with Henry, who was also a radical, public school teacher, and Union member, she co-founded in 1936 the journal Science & Society, which claims distinctino as "the longest continuously published journal of Marxist scholarship, in any language, in the world" (http://www.scienceandsociety.com/).

[2] Subversive Influence in the Educational Process: Hearings before the United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary, Subcommittee to Investigate the Administration of the Internal Security Act and Other Internal Security Laws, Eighty-Second Congress, Second Session, Eighty-Third Congress, First Session (Washington, D.C.: U.S. G.P.O., 1952-53). The report is in the public domain and is accessible on any number of platforms, including HathiTrust. Henry's testimony appears on pp. 51-56.