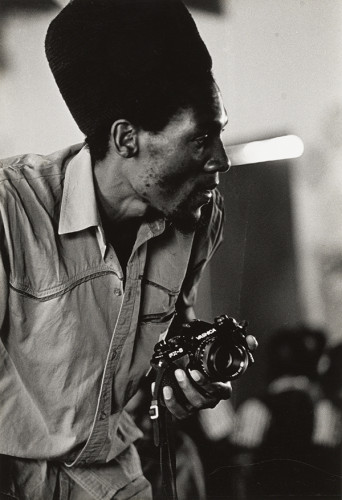

In celebration of International Archives Week, we are delighted to highlight the Chicago Dzviti Photograph Collection. In 2018, Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation (RBSCP) at the University of Rochester received a notable collection demonstrating the remarkable photographic works of Chicago Dzviti, who documented Zimbabwean life and culture in the 1990s. RBSCP is humbled to be the responsible repository of Dzviti’s photographic archive.

Dzviti was a photographer, journalist, pioneer, husband, and friend. The following are the reflections on his life and legacy by those who knew him or his work.

Reflections by Lorraine Chitungo, Chicago Dzviti’s widow

What was your relationship like with Chicago?

My relationship with my husband, the late Baba Dzviti, was the best thing that ever happened to me as if we knew we were not going to be together for long. Knowing that his work is what buttered our bread, I fully supported him with love and would wake up early to clean his darkroom, and would sometimes even joke around with him.

Chicago’s photography studio was in your home, were you ever part of the creative process?

He had an eye that would see beauty in what others thought as mere nothing. He knew what he wanted and would go for it. So I would say I was part of his creative process to a lesser extent.

Why was it important to you to have Chicago's photographs archived in an educational institution?

Having his photographs archived means a lot. It means his work will live forever, and many generations will be able to see them and even learn from and about them. It gives us hope that even though he is gone, his work still lives, so I would say the benefit of having them archived is LEGACY.

Reflections by Chartwell Dutiro, friend and musical collaborator

What was your relationship with Chicago Dzviti?

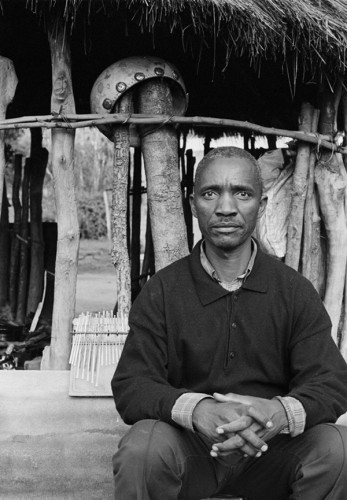

Chicago Dzviti was a personal family friend. We hung around together in the 1990s; he would come with his camera to the gigs of Thomas Mapfumo and The Blacks Unlimited mostly around Harare. He took some beautiful photos, both at gigs and family photos for me. It was towards the end of 1993 that my best friend Richard Selman visited Zimbabwe for the first time. Earlier that year, I put together an itinerary of a number of mbira makers, and I thought he also needed a good photographer to document his research. This was when I introduced Chicago to Richard. My two special friends and I thought it was a meeting made by ancestors. The book, Making Lamellaphones: Instruments of the mbira and Kalimba Families, Contemporary Variants, co-author Bart Hopkin and Richard Selman, was published in 2016. It is immaculately written and overdue research about leading fabulous Shona mbira makers from Zimbabwe. Some of the photos in the book are by Chicago Dzviti.

It was with deep pleasure to have worked with Chicago. I was part of a USA tour that took both Chicago Dzviti and mbira maker Chris Mhlanga first out of Zimbabwe in 1998.

What do you see as a benefit in having Dzviti's photographs archived?

I am pleased to see that Chicago's photos are archived and accessible for research purposes. I also think that it will be a great empathy if the University [of Rochester] can facilitate a link with the Zimbabwe National Archive and maybe a repatriation of some of the photographs back to Zimbabwe to deal with the issues of intellectual property/copyright, so that things are transparent for all involved and we deal with issues of Cultural Appropriation.

Chicago Dzviti R.I.P., you are missed, but we feel your spirit.

Reflections by Calvin Dondo, photographer and friend

What was your relationship with the photographer, Chicago Dzviti?

It was an honor to work with Chicago Dzviti. He was a gifted photographer and my best friend, who played a big role in the development of photography in Zimbabwe and Africa. I had an opportunity to show his work in the biggest African photography exhibit in Bamako Encounters in Mali, it was warmly received and was included in a traveling show in Europe.

We wanted to take photography in Zimbabwe to new heights as best friends, and he left me with a big task to further this onerous task. He was a great photographer.

Why was Chicago’s work so special?

Chicago was a photographer who believed in and respected the communities he worked with. The mbira project, which was one of the bodies of work he produced, was a beautiful and pioneering project in Zimbabwe by a black photographer. And it was done by a photographer who was very sensitive about the role mbira music plays in the spiritual culture of Zimbabwe.

He managed to travel and document some of the spiritual mbira musicians around the country without a project budget, with only inspiration and enthusiasm to give. His work with the musicians highlights their talents and their role as custodians of Zimbabwean culture.

What do you see as a benefit in having Dzviti's photographs archived and accessible for research purposes?

I hope archiving his work will benefit a lot of people. It speaks about both mbira music and the history of photography in Zimbabwe pre and post-independence. The work he did will serve as a light to musicians, students, researchers and to people who want to know more about mbira origins and contemporary mbira music players.

Reflections by Jennifer W. Kyker, Associate Professor of Ethnomusicology*

What was your relationship with Chicago Dzviti?

It is a crazy story, and it starts a zine that was published in the 90s by a guy in Seattle to connect people who were playing Zimbabwe music. I was a teenager at the time that this magazine was circulating, and I read it. This is where I first encountered Chicago Dzviti. First, they published an article by Chicago, featuring his photographs of the Zimbabwean Mbira player, Sekuru Chigamba, and then the next thing, they published an obituary and biography of him by his friend Richard Selman.

What was Dzviti’s relationship with the subject of his photographs, was he a musician as well?

No. I think he was interested in culture more broadly. The visual images are very striking. He covered all these cultural events from world press photo events where there are traditional musical groups to things like the book fair and craft shows. He is obviously someone who wanted to portray Zimbabwe not as either traditional or modern but as tradition existing and flourishing in the present, as something alive. Rural life as something that is contemporary and not outdated, and mbira as modern and not only of the past. I think in his photographic eye, you see this vision of someone who understands the importance of culture as part of the modern world.

When you look at his photographs, what do you see?

You know, it’s been wild for me processing this material, and going through all the photographs. When we got the material there was no order. I went through to figure out what negatives belonged to the same roll and which prints belonged to the various negatives. The prints in the collection are his that he printed in his home darkroom. He took photography at the Harare Polytechnic Institute; he knew how to create a high-quality darkroom.

I’ve gone through the material dozens of times, and each time it is very moving. The time period he was working in was the early 90s, before the political change in the late 90s. He didn’t get to see that, that is not part of this visual record. This is a visual record that still belonged to the optimistic days of the first 15 years after Zimbabwe’s independence.

How has working with the material been beneficial for your research?

I have used a lot of the photographs in the current digital humanities project I’m working on [Sekuru Stories]. I am writing an article about a popular Zimbabwean singer, who was a comedian and a pioneering Zimbabwean entertainer, first Black professional entertainers in Zimbabwe, in the 50s and 60s, and of course, Chicago had taken his photo. Just being able to show people the artists that I am talking about and the instruments I am discussing is wonderful. We have a privileged view of a Zimbabwean representation of Zimbabwe, which is not that common. So often Zimbabwe is being represented by outsiders. Here we have and a Zimbabwean authorial eye, right, that can show us what he thinks is important.

Why was it important for you to preserve this collection?

There has been a resurgence of interest in African photographers and African photographs. Mali is a country that is well known for it’s especially studio photographers, people like [Malick] Sidibe. In a way I thought here is Zimbabwe’s unsung Sidibe.

I think there will be interest in the collection. The photographs could speak to a wide audience. A digital project is in order. One of the things I most want to do is a repatriation project. A lot of the individuals in these photographs are identified or identifiable. It would be amazing to be able to make prints and give them to the artists who are pictured in them, or if the artist has died, their family members. I think it would be a really meaningful project and a way to follow up on how this musical scene that Chicago was so interested in documenting looks 25 years later. It would be a great way to open up a conversation with people around music in their family and music making, instrument making, and historical change.

This collection is personal for me. Teachers, people I have stayed within their homes, people who have since passed on, are in this collections. It can be heavy in some ways, but wonderful in so many others, to see people I loved so dearly.

*A longer version of the interview with Jennifer Kyker has been transcribed and can be found in the collection.

A Portrait of Zimbabwe: The Chicago Dzviti Photograph Collection exhibit, curated by Jennifer Kyker, represents the breadth of Dzviti’s photographic vision. It is on display in the Freelander Gallery of the Rush Rhees Library though September, 2019.