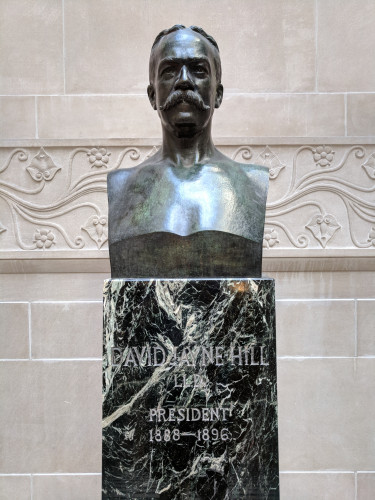

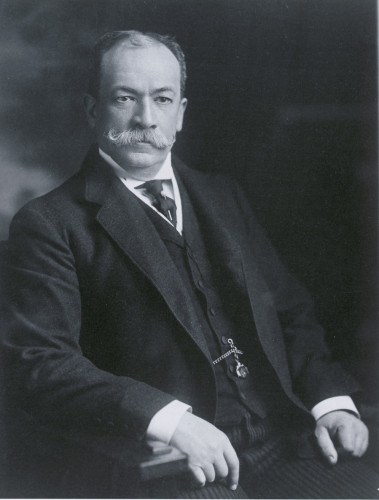

Although he would only serve for seven years - one-fifth the tenure of his predecessor, Martin Brewer Anderson - Hill would make important changes and lay the groundwork for the transformative efforts of his successor, Rush Rhees.

According to biographer Aubrey Lawrence Parkman, when Hill took office the University of Rochester was "struggling to hold its own, and barely doing that. There had been no material increase in the yearly attendance of students, its out-of-town enrollment was dwindling..."

Hill found local financial support for the University to be minimal; an alumni base dedicated more to the memory of President Anderson than to the institution; a faculty and Board of Trustees more ready to accept direction than collaboration and a student body in need of direction and a wider more modern range of courses.

When Hill left in 1896, some of the innovations Hill introduced or suggestion he approved included organized athletic teams and an Extension School providing lecture series to the general public. Academically "separate departments of physics, geology, and biology were created, and the laboratory study of these subjects was introduced for the first time," and the faculty were taking an active role in setting the curriculum and introducing new courses.

Perhaps most memorably, in 1891, Hill provided a welcoming ear to Rochesterians who sought admission for women to the University. Juliet Hill had recently given birth to twins--a girl and a boy--and President Hill reportedly told a gathering at the home of Susan B. Anthony that “if the Creator could risk placing sexes in such near relations…they might with safety walk on the same campus and pursue the same curriculum together.”

Hill's views on coeducation should not have been a surprise: in 1883, four years into his 10-year presidency of Bucknell University, women were admitted to that school, making Bucknell the 14th coeducational institution of higher education in the US.

Women would gain admission at Rochester in 1900. Like Rush Rhees, Hill preferred a coordinate system (i.e., a College for Men and a separate College for Women) which the UR would adopt in 1913.

Two years after resigning from Rochester, Hill was appointed as an Assistant Secretary of State (1898-1903), then became US Ambassador to Switzerland (1903-05), to the Netherlands and Luxembourg (1905-08), and to Germany (1908-1911). His papers in the University Archives contain correspondence with Theodore Roosevelt and Andrew Carnegie.

Hill was on hand for the cornerstone laying of the School of Medicine and Dentistry in 1923, and would live to see the University expand to include the Eastman School of Music and the Institute of Optics.

Hill planned to attend the dedication of the River Campus in October 1930, but business in Washington, D.C. detained him. He died on March 2, 1932.

Read Parkman's article in the Library Bulletin: https://uorrcl.access.preservica.com/uncategorized/IO_ec2e5c85-2166-47cc-a6e8-21e32ad21341/, and watch for the upcoming exhibit, "To Reach Our Farthest Star: Leading the University of Rochester, 1850-2019" opening later this summer in the Great Hall of Rush Rhees Library.