My Father, a historian, always told me that 90% of history work is brute-force research: going through letter after letter and diary after diary to find evidence or information. Though it may be arduous at times, this sort of work is essential to piecing together accurate histories. When I was assigned to look through the Porter Family Collection this semester, I did just this.

The Porters and their relatives by marriage, the Farleys and Pecks, were all active in Rochester’s reform movements, especially the abolitionist movement. Notably, Samuel D. Porter and his wife, Susan Farley Porter, helped people born into slavery escape to Canada through a nearby barn belonging to his sisters. Maria Porter, Samuel D. Porter’s sister, was the treasurer of the Rochester Ladies’ Anti-Slavery Sewing Society, and was heavily involved in the organization from its founding. Though some members of the family were more involved in reform movements than others, reading their letters proved that the Porters tended to enthusiastically support one another’s pursuits, abolitionist or otherwise.

For my first task, I was asked to find a precise date range for when Betsey Farley, mother of Susan Farley Porter and Joseph Farley, moved to Rochester. Susan F. Porter and Joseph Farley, Betsy’s children, both married Porters: Susan wed Samuel D. Porter, and Joseph Farley paired with Laura Porter (later Laura P. Farley). As a result, the Porter Family Collection contains extensive correspondence between the couples and their brothers and sisters.

When, after reading the first few folders of letters, there seemed to be no mention of “Betsy” Farley, I realized that her children and their spouses may have been calling her by a different name, and began to look for mentions of “mother” instead of “Betsy Farley.” Through this investigation, I found that though Joseph Farley referred to Betsy Farley simply as “mother,” Laura Farley, her daughter-in-law, would solely write about her as “Grandma Farley,” “Mrs. Farley,” or “honored mother.” This discovery was essential to figuring out when Betsey moved to Rochester: using these titles, I was able to find the first instance where Betsey Farley had come to Rochester to stay. Remarkably, it came in the form of a letter from Elizabeth Porter describing the domestic scene at Joseph and Laura Farley’s home, written on August 29, 1843:

Libby sits making jacket and trousers but has to look up and express her admiration of his horsemanship- Laura will, I guess, be washing little Delia who laughs and plays all the time and looks like a beauty- she is the sweetest little creature I ever saw- Porter stands by admiring his “dear little sister,” wanting everyone to “come look at her dear little head or her dear little foot,” and to finish the picture grandma Farley sits in the rocking chair knitting- Joe has gone today to Honey Cough flats and has taken Jane Hart with him- they are all very well.

Though this passage may seem mundane, it brought me a wealth of information: since it was the first mention of Betsy Farley being in Rochester and is followed by continuous mentions of her presence, I was able to decipher that Betsy Farley had moved to Rochester by 1843. Gleefully finishing that portion of my research, I moved on to my next task.

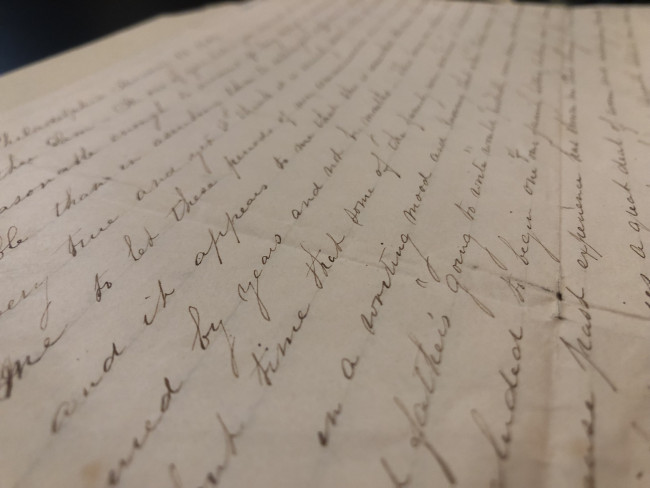

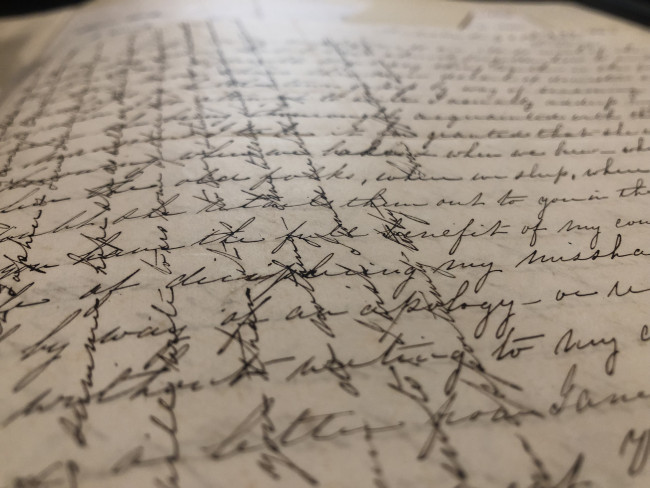

[Elizabeth Porter often writes with overlapping handwriting to allow for more content over less space. Though it is beautiful, I found it to be difficult to read at times]

The patron request for information on Betsey Farley continued with an interesting question regarding the Porter’s involvement with the Underground Railroad: was there any evidence to suggest that they had been selling property to fund their Underground Railroad undertakings? Since this question involved a more vague date range, we pulled five boxes from the Porter Family Collection for my research purposes, and I got to work.

The sheer amount of letters that I had to read felt overwhelming at times. For a while, I found hardly any mention of abolitionism, the Porter’s Underground Railroad endeavors, or activism; soon I realized it was because I was slogging through too many letters from the wrong time period. When I switched to the 1840s and 50s, more information cropped up, but I was unable to prove that the Porters had specifically sold property for the purpose of funding the underground railroad. I did, however, make several other interesting findings

For one, the Porters were a generous family: when a black man named Harrison Powell was having trouble collecting debts from a white man, Sam Porter stepped in to help. In February of 1842, Samuel Porter wrote to his father in Philadelphia that recently, a man named Harrison Powell had purchased some property from Samuel, but needed to collect money from a man in Philadelphia that had bought a house from Powell, never paying him fully. Throughout the year 1842, correspondence between Samuel Porter Jr. and Sr. was filled with dialogue about getting Harrison Powell his money- eventually, by July, Samuel D. Porter Sr. had successfully obtained the checks and sent them to Rochester. After this exchange, there was no longer much mention of Mr. Powell.

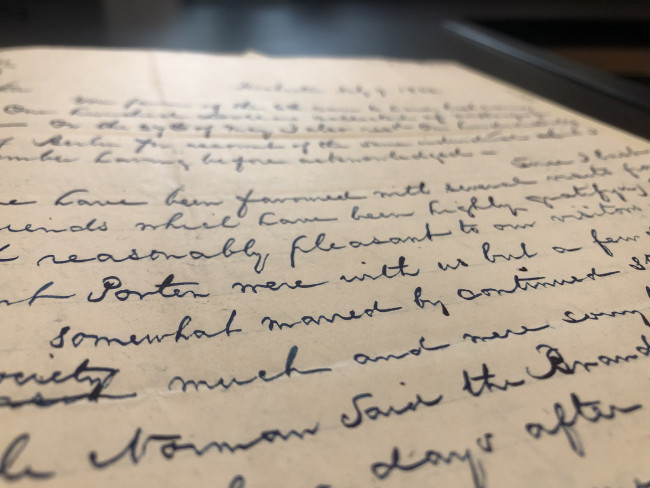

[Here, Laura Farley writes to her brother, describing a lovely Christmas and New Year’s.]

In the 1840s, the Porter’s willingness to go out of their way to help a person of color was exceptional. Though slavery was outlawed in New York in 1827, slave-catchers were allowed to travel north to capture those who had fled southern states. On top of that, prejudice and racism was widespread, and the city of Rochester had separate sections for the “colored population.” People like the Porters, however, were there to change that. Along with Frederick Douglass and other abolitionist Rochesterians, including the Anthony and Post families, the Porter family attended anti-slavery conventions and did whatever they could to support equality for all. In one 1843 letter from Elizabeth Porter to her father, Samuel Porter, she wrote:

A state anti-slavery convention of coloured citizens met here last week and I wish you could all have been present to see the decorum and dignity with which they conducted their meeting, and the grace and eloquence with which they carried on their debates. It has had a great effect on the community here, and has done more to overcome the wicked prejudice against colour I entertained by so many than all meetings previously held.

Perhaps the most compelling aspect of my research with the Porter collection was the pure human connection I witnessed: strong, loyal, and loving ties between family members. As I perused hundreds of letters between Porters, Farleys, and Pecks, I watched them age with my own eyes, observing their progression from young, newly married couples to middle-aged parents. In January of 1844, Laura Farley wrote to her brother Samuel, reminiscing on their age(though they were both hardly past age thirty). Perhaps missing more regular communication with her brother, who lived in Philadelphia, she wrote on January 17, 1844:

My dear brother Sam-in one of your letters you remark that we are both old enough and reasonable enough to account for long delays in writing in ways far more comfortable than ascribing them to estranged affection or forgetfulness- This may be very true and yet I think it is scarcely worth while for reasonable you and me to let these periods of no communication run to an unreasonable length and it appears to me that this is somewhat the case when they are to be measured by years and not by months…

Above all, the Porters were filled with generosity, strong values, and a belief in the importance of family. As I progressed through their personal letters, searching for various aspects of their lives, the most notable facet of the Porters was the level of closeness they maintained throughout life despite long distances, war, and death. And that, readers, is the reason I do history: to witness the continuity of human connection, love, and family.

By: Eleanor Lenoe '21