Back in April, RBSCP's social media manager asked if anyone in the department knew any poems in the collections that they'd especially like to share for National Poetry Month.

I responded to the email so fast that if we'd been talking in person I might have jumped to my feet. Yes, I did know exactly the poem. It had been echoing in my head ever since I'd read it while processing gay community leader RJ Alcalá's materials. Actually, I had a picture of it on my phone. And yes, I would gladly write about it.

I wrote the post from memory. And yet, when I went back to get a better photo of the pamphlet, I found myself hesitating. The poem was written by members of a revolutionary gay men's collective from New York City who had gone to Cuba in 1970 to participate in the Venceremos Brigade and been told that their support was not welcome.

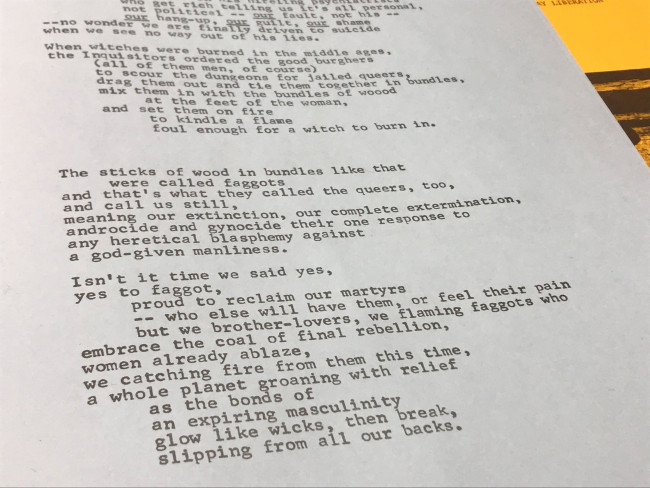

Everything that spoke to me — its rawness and immediacy, its vibrant anger, its plain-language thirst for action to dismantle an unjust world and the bigotries which have for so long been authors of violence, oppression, and fear — all these things that I loved about the poem were the same things that made me question if I wanted to hang it out on Facebook, sans much of its context, for anyone to see.

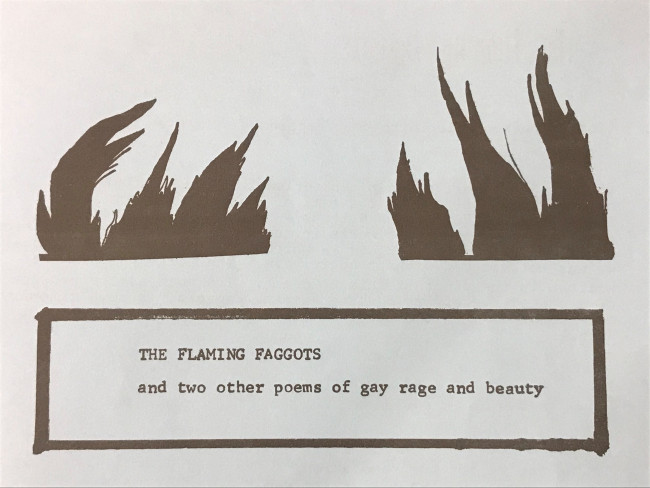

Compared to the other upbeat things on the page, this one would be a visual suckerpunch. The poem, and the group who wrote it, are both called "The Flaming Faggots."

Passage from the poem 'Flaming Faggots"

As a self-described queer punk, I felt a lot of conflicting things about that hesitation, and about the reasons behind it.

Whenever I tell people I'm queer, I have to watch for their reaction to that reclaimed slur. How likely was it that people seeing the post would understand the aggressive triumph of the writers' reclamation of "faggot"? Would showcasing that word hurt other LGBTQIA+ folks who have had it used against them? Would the righteous, searing anger that resonated so deeply with me be too out of the blue, read as the misplaced shouts of one more irrational "angry queer"? Was I going to get another talking-to for being too aggressive, too political? Why couldn't I focus on something happy? And maybe it wasn't, I thought as I read it over again, really that good of a poem. It could be tighter — it suffered a bit from going on and on when it could have been punchier.

It felt like the end of a long rough day when your emotions are running over and your mouth keeps going because you're in pain and the filter's come off and someone's asked how you're doing. It was nearly five pages long.

Did I really want to use this as my exemplar of queer protest poetry? I thought of how difficult it can sometimes be to communicate clearly when you're so stressed from every direction. Would I be doing these activists — the LGBTQIA+ community at large, whether they had anything to do with it or not — a disservice? Did I even have the energy to navigate all of this right now???

At the same time, I very much wanted to share this deep moment of recognition I'd felt with other queer folks. This moment of holding the past in my hands and seeing my own heart in it was the singular reason I became an archivist. Was I seriously going to participate in the censoring of the pain and outrage of those who came before me?

When archivists preserve records of the past, we are under an edict not to gloss over or misrepresent the parts of that history that we find uncomfortable or unpleasant. This goes right up to not changing words which have loaded connotations. Participation in the erasure only serves to reinforce a harmful status quo, to the benefit of the oppressors.

At the same time, as archivists we are aware that working with original materials is very different from working with secondary sources: the emotional rawness and impact of the original creators is still in the present tense in the archives, without the benefit of the blurring lens of someone's interpretation to provide distance, or the couching of additional context for clarity.

We understand that what we see in these collections is one leaf out of a large forest of context and causality, and from there are able to critically analyze the materials. We (have to) understand that no one voice speaks for a whole community, and that the community-as-monolith is a myth.

And yet.

Ultimately, I found another piece to highlight for April. It's an excellent piece, and I would have been glad to highlight it any time of the year. It is, perhaps, less "unpleasant" than the Flaming Faggots poetry, and appeals to a wider audience. But I still thought a lot about that poem, and the people who wrote it, and whether listening to those anxieties and deciding not to feature it then was censorship, avoidance, or protection. Whether I was being a good member of the queer community, and a good activist.

It's Pride Month. I've been lucky enough in my life to work with a lot of archival materials from the LGBTQIA+ community, and I probably understand more than most that even though the image of a homogenous, unified front is an artificial construction, sometimes it's one built by a group banding together for the purposes of defense and strength in numbers.

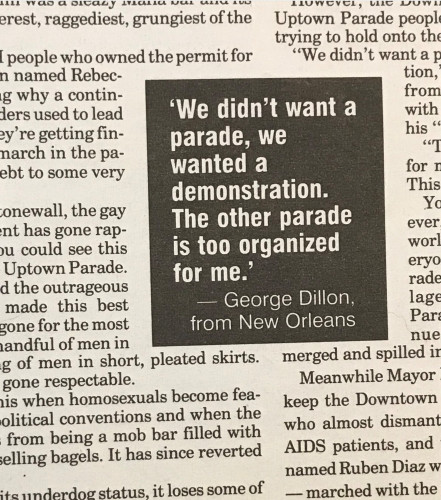

The self-policing that members of persecuted groups enact on each other, which is born out of a protective instinct in oppressive circumstances, has seen generational cascades through the LGBT rights movement as it has in the civil rights movement, women's rights movement, and revolutions all over the world. It's the same thing those Cuban revolutionaries told the Flaming Faggots in 1970, that sparked their poem. Over and over we are told we can only push the envelope so far, that only so much "extra" divergence from the mainstream is acceptable. But anger and pain are also important and valid parts of the human experience- and thus, important parts of the archive.

Quote from newspaper feature on the "unauthorized" march to commemorate Stonewall, June 27th, 1994. RJ Alcalá gay rights and culture collection, D.602

I watch companies splashing rainbows and the faces of activists whose work has still not been fulfilled on their products for profit, rather than making true change, I think about how the anger and love of those activists — and of the activists of today— still feels like transgressive territory. We have a lot to celebrate, and Pride should be a fierce and righteous celebration. It's especially renewing to look back at the archived materials from the victories the LGBTQIA+ movement has gathered along the way and feel the rush of joy captured in those moments. But the fact that we're still angry should also tell everyone that there's still things that need to be done, and until that time, this anger has a valid place at Pride, too.

A full scan of the Gay Flames Pamphlet no. 12 is accessible on JSTOR. https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.28037169