Batty Langley (bap. 1696-1751).

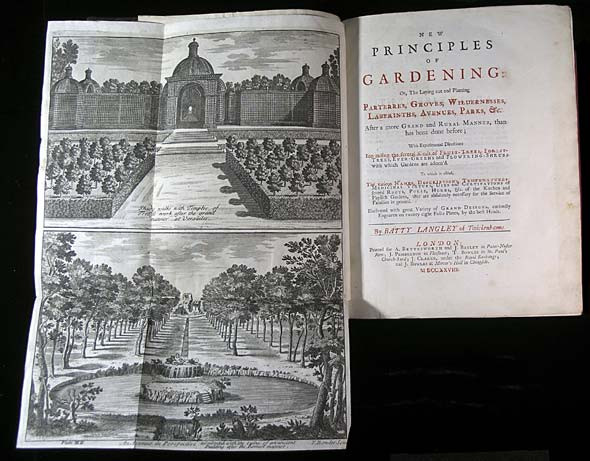

New Principles of Gardening, or, the laying out and planting parterres, groves, wildernesses, labyrinths, avenues, parks, & c. London: A. Bettesworth and J. Batley, 1728.

New Principles of Gardening is profusely illustrated with 28 copperplate engravings. It contains meticulous descriptions of how the principles of geometry can be applied to the design of gardens, including rules on the location and arrangement of gardens in a rural setting. There are instructions about the planting and care of fruit trees, forest trees, and shrubs. The illustrations describe geometrical diagrams, garden plans, and designs of ruins suitable for the end of walks.

The author of this treatise is Batty Langley (bap. 1696-1751), a popular writer on architecture and landscape designer. The dedication is presumably addressed to King George II, who succeeded to the throne on 11 June 1727.

Many English aristocrats who experienced the so-called Grand Tour, a long educational journey through Mediterranean countries such as Italy and Greece, might have welcomed versions of Roman ruins.

Inspired by the gardens at Versailles, Langley occasionally tried to improve their design.

In the first half of the eighteenth century, England saw a revolution in garden design. The traditional rigid geometrical layout was gradually replaced by plans that aimed to replicate the intrinsic irregularities of nature. This particular trend in practical horticulture was the result of a new intellectual climate: artists and writers began to question old assumptions concerning the relationship between nature and art. By criticizing the excessive artificiality of art, some intellectuals advocated the idea that any artistic representation should accurately imitate the "simplicity" of nature. For instance, in an essay published in The Guardian (No 173, September 29, 1713), Alexander Pope recalls the natural harmony of the gardens described by Homer (the garden of King Alkinoos, Odyssey 7.112-32) and Vergil (the garden of the old Corycian, Georgics4.125-48) as models that garden planners should follow. Indeed, Pope strongly contrasts the idyllic ancient garden (locus amoenus) to those of his own time:

How contrary to this simplicity is the modern practice of gardening; we seem to make it our study to recede from nature, not only in the various tonsure of greens into the most regular and formal shapes, but even in monstrous attempts beyond the reach of the art itself: We run into sculpture, and are yet better pleased to have our trees in the most awkward figures of men and animals, than in the most regular of their own.

In The Spectator (No 414, 25 June, 1712), Joseph Addison expressed analogous views, again highlighting the notion that the art of gardening should learn from nature itself:

We have before observed, that there is generally in nature something more grand and august, than what we meet with in the curiosities of art. When, therefore, we see this imitated in any measure, it gives us a nobler and more exalted kind of pleasure than what we receive from the nicer and more accurate productions of art. On this account our English gardens are not so entertaining to the fancy as those in France and Italy, where we see a large extent of ground covered over with an agreeable mixture of garden and forest, which represent every where an artificial rudeness, much more charming than that neatness and elegancy which we meet with in those of our own country.

An important French treatise on garden design somehow anticipated some of the ideas expressed by Pope and Addison: A. J. Dezallier d'Argenville's La theorie et la pratique du jardinage (Paris: J. Mariette, 1709). This work deals with the design of the so-called "pleasure gardens," including the making of parterres, mazes, garden buildings, and many other ornaments. John James (c. 1672-1746), architect, surveyor, and carpenter, wrote the first English translation of d'Argenville's work: The theory and practice of gardening (London: Maurice Atkins, 1712). From the English perspective, one of the most interesting technical innovations presented in the book is the ha-ha. Originally used by the French army, the ha-ha is a hidden trench that works as a barrier for grazing livestock without blocking the view of a landscape. The English translation keeps the original French term ah-ah:

Grills of iron are very necessary ornaments in the lines of walks, to extend the view, and to shew the country to advantage. At present we frequently make thoroughviews, call'd Ah, Ah, which are openings in the walls, without grills, to the very level of the walks, with a large and deep ditch at the foot of them, lined on both sides to sustain the earth, and prevent the getting over; which surprises the eye upon coming near it, and makes one cry, Ah! Ah! from whence it takes its name. This sort of opening is, on some occasions, to be preferred, for that it does not at all interrupt the prospect, as the bars of a grill do.

Unquestionably, by describing how to create a smooth transition between the garden and the countryside, the new treatises on horticulture to some extent reflected the theme that art should imitate nature. These new ideas could be also found in the written work of the landscape designer Stephen Switzer (bap. 1682-1745): The Nobleman, Gentleman, and Gardener's Recreation, or, an introduction to gardening, planting, agriculture, and the other business and pleasures of a country life (London: B. Barker and C. King, 1715), and Ichnographia Rustica; or, the nobleman, gentleman, and gardener's recreation (London: D. Brown, 1718). Switzer argues that, whereas a little regularity should be allowed near the house, the designer should always follow the inspiration of nature:

To come nearer our purpose, if a litt'e regularity is allow'd near the main building, and assoon as the designer has stroke out by art, some of the roughest and boldest of his strokes, he ought to pursue nature afterwards, and by as many twinings and windings as his villa will allow, will endeavour to diversify his views, always striving that they may be so intermixt, as not to be all discover'd at once; but that there should be as much as possible, something appearing new and diverting, while the work should correspond together by the mazie error of its natural avenues and meanders.

Similarly, in his introduction to New Principles of Gardening, Langley declares:

For since the pleasure of a garden depends on the variety of its parts, `tis therefore that we should well consider of their dispositions, so as to have a continued series of harmonious objects, that will present new and delightful scenes to our view at every step we take, which regular gardens are incapable of doing. Nor is there any thing more shocking than a stiff regular garden; where after we have seen one quarter thereof, the very same is repeated in all the remaining parts, so that we are tired, instead of being further entertain'd with something new as expected.

Langley argues that a garden should consist of what he calls "regular irregularity." This idea is exemplified in the instructions for the plantation of groves:

In the planting of groves, you must observe a regular irregularity; not planting them according to the common method like an orchard, with their trees in straight lines ranging every way, but in a rural manner, as if they had receiv'd their situation from nature itself.

Furthermore, Langley recommends that views should be as far-reaching as possible, being an advocate of the so-called ha-ha. In the plate included below, one can see a plan for the improvement of the garden at Twickenham. The suggested ditch, which is indicated by the letter R, will facilitate the view of the long walk from H to K: "At R, there is a Ha, Ha, of water, which is a fence to the garden from the road, and admits of a nicer view, which iron gates or grills cannot do."

Our volume is bound in full calf, in what is generally known as the Cambridge panel style. This binding design came into fashion c. 1690, and was especially popular until 1740. Its main characteristic is the presence of three concentric panels, and the creation of a multi-tone effect by sprinkling the panels with ink or acid. As a result, the binder would create a stained central rectangular panel surrounded by a plain rectangular frame, which, in turn, is surrounded by a stained panel. The additional decoration in our volume is one popular variant within this binding style. Both covers are decorated with two-line fillets and flower rolls close to these lines. As David Pearson mentions in his English Bookbinding Styles, 1450-1800: A Handbook ( London: British Library; New Castle, DE: Oak Knoll Press, 2005), the expression "Cambridge panel style" is inadequate since this design was used in all English bindings centers, not just in Cambridge. Besides, there is no evidence that it originated there.

Finally, we must add a few notes on the provenance of this volume. New Principles of Gardening was formerly owned by Elizabeth G. Holahan (1903-2002). Ms. Holahan was born in Mumford, NY, in 1903. She was raised in Rochester, and was educated at East High School and the old Mechanics Institute (now the Rochester Institute of Technology). Although she was by profession an interior decorator, her life-long interest was centered in the restoration and renovation of historical sites and buildings in the Rochester area. She served as president of the Landmark Society of Western New York from 1954 to 1962, and was president of the Rochester Historical Society from 1977 to 2000. Ms. Holahan was also involved in several initiatives launched by the University of Rochester. In 1962 the beautiful Patrick Barry House on Mt. Hope Avenue was given to the University of Rochester. Ms. Holahan was commissioned for the restoration and renovation of the interiors of this building (1963-65). This house has great historical interest: it was originally designed by the famous English architect Gervase Wheeler and built in 1855-7. Ms. Holahan was also actively involved with the Friends of the Library of the University of Rochester for a number of years.

In 2004, the Department of Rare Books, Special Collections and Preservation, at the University of Rochester, received part of Ms. Holahan's library through a gift from the Rochester Area Community Foundation. These books are not only a faithful testimony to her passion for architectural preservation, but they also reveal a wide range of intellectual interests, including horticulture, travel literature, eighteenth-century architecture, British literature, European and American history, fine arts, and, particularly, the intellectual circle of Samuel Johnson. Many of these titles perfectly match the current collecting interests of our library. For instance, the books on gardening are a wonderful addition to our collection of horticultural books. Our department houses the archives of the Ellwanger and Barry Company, founded in 1840 as the Mt. Hope Nursery by George Ellwanger and Patrick Barry. These archives include the firm's library: a collection of 560 titles (1,600 volumes), particularly strong in nineteenth-century horticultural books. Ms. Holahan's books on horticulture will complement the working library of the Ellwanger and Barry Company, which is especially fitting as she was involved with the history of the Barry family through the restoration of their house on Mt. Hope.

This blog entry was originally contributed by Pablo Alvarez, Curator of Rare Books at the University of Rochester from 2003 to 2010.

Select Bibliography

Blanche, Henrey. British Botanical and Horticultural Literature before 1800. Comprising a History and Bibliography of Botanical and Horticultural Books Printed in England, Scotland, and Ireland from the Earliest Times until 1800. 3 vols. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1975.

Dezallier d'Argenville, A. J. La theorie et la pratique du jardinage. Ou l'on traite a fond des beaux jardins appellés communément les jardins de propreté, comme sont les parterres, les bosquets, les boulingrins, &c. Contenant plusieurs plans et dispositions generales de jardins; nouveaux desseins…& autres ornemens servant à la décoration & embélissement des jardins. Avec la maniere de dresser un terrain… Paris: J. Mariette, 1709.

________. Trans. John James. The Theory and Practice of Gardening: wherein is fully handled all that relates to the fine gardens, commonly called pleasure-gardens, as parterres, groves, bowling-greens…: together with remarks and general rules in all that concerns the art of gardening. London: George James, 1712.

Matthew, H.C.G and Brian Harrison, ed. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography: in Association with the British Academy: from the Earliest Times to the Year 2000. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Pearson, David. English Bookbinding Styles, 1450-1800: A Handbook. London: British Library; New Castle, DE: Oak Knoll Press, 2005.

Switzer, Stephen. Ichnographia Rustica: or, the nobleman, gentleman, and gardener's recreation. Containing directions for the general distribution of a country seat into rural and extensive gardens, parks, paddocks, & c., and a general system of agriculture; illus. from the author's drawings. 3 vols. London: D. Browne, 1718.