For Women's History Month, RBSCP is featuring the collection of Mollie Moon, a glittering, tireless spirit in civil rights and social justice history.

Old photographs always really get me. Especially in shots where there’s something of a candid element, photographs provide one of the most palpable moments in historical materials where the people in the records come alive. You can read a lot of personal notes and biographies and summaries of a person’s work, but seeing a picture of them where you know some word has just left their lips, where their expression tells you they’re expecting something to happen next – all of a sudden their lives feel more tangible and real. They lived, and breathed, and had conversations with the photographer, maybe, and had expectations and futures. A lot of times we don’t know who the people in the photographs we have in the archives are, which lends something a little haunting to them. I always get caught thinking about who they were, who they became.

With this collection though, I’m thankful to say we know exactly WHO the woman featured is.

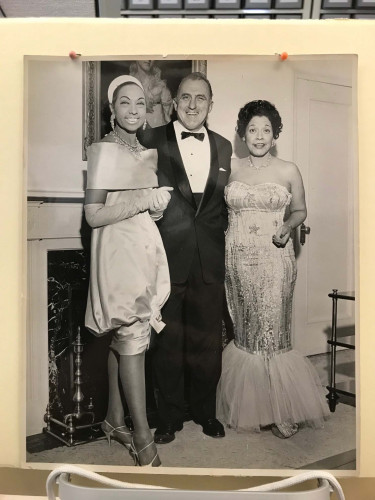

[Right to left: Mollie Moon, Walter J. Hausman, Jr. and Josephine Baker at the Hotel Roosevelt during the National Urban League’s 1960 Beaux Arts Ball, New York City. Photograph by Cecil Layne.]

In the 1956 studio portrait photo of Mollie in this collection- which was taken either slightly before or after the one featured on her Wikipedia page, in the same sitting- she sits posed looking off to the left, a classical figure. She has a slight smile, a little patient, the kind of smile that feels like it says, “Alright, I’ll wait.” In the second photo, however, her eyes are raised just a little bit over and to the left of the cameraman, her outreached hand turned palm-up as if in question, her eyebrows arched, her expression bright. To her right performer and activist Josephine Baker and director Walter J. Hausman, Jr. are laughing merrily. The three of them may be posed there by the fireplace for the photo, but the sounds of the Beaux Arts Ball are almost audible there around them, whatever Mollie has just asked still ringing in the air.

We don’t have to look far to hear more of her voice, either. In the third and final item in the collection, a three page letter written in 1945, she writes about family and friends; she relates the goings-on of her “crazy cousins” (including writer Chester Himes, who also figures in the collections here); she talks about being able to sleep better knowing that her “Darling Baby” has arrived safely after travel. She signs it, “Be sweet & do a good job- All My Love- Mollie.”

Mollie Moon was the founder and long-time president of the National Urban League Guild, the organization which funded the racial equality work of the National Urban League. She held graduate degrees in pharmacy, studied social work, housing, and public relations, was fluent in German, and studied biology and education in Berlin. When she left pharmacy to become a social worker for the Department of Social Services in New York City in 1938, she established herself as a distinguished member of the National Urban League and New York high society, working to improve race relations and equity for Black Americans. In her own words, she said:

“At an early age I became aware of my obligation to participate in organized efforts to level the onerous barriers which locked me and my people in a ghastly cultural, political, and economic ghetto. Neither I nor my family had sufficient income to make significant financial contribution to this cause. We did, however, have commitment, energy, and time to contribute.” (Questionnaire, Fisk University Library, May 27th, 1982).

It was Mollie Moon who first sponsored and began the annual National Urban League’s black tie Beaux Arts Ball, now a fixture of New York tradition. Through the Ball and other endeavors Mollie was responsible for raising more than $3.4 million for the National Urban League. As much as she is remembered as a high society figure and socialite, she was also an ardent activist, community builder, civic worker, and humanitarian. She was recognized by an international community of volunteer service organizations, governments, and charities, and was the recipient of nearly as many awards as lines in this blog entry. Several awards recognizing individuals who have made outstanding contributions to the advancement of Black people and community service have since been named for her. She was, by any stretch of the imagination, a giant. And yet in these photos she seems like she could walk into any room you might be in and belong there, too.

![[Be sweet & do a good job – All my love – Mollie.”]](/sites/default/files/styles/honeycomb_media/public/images/Image%203_8.jpg?itok=82HgZ-vv)

[Be sweet & do a good job – All my love – Mollie.”]

In a world where so often the forces of corporations and governments and tides that seem to sweep through without our control can make it seem like we are just small voices against so much, seeing Mollie as a real person doesn’t feel like bringing her achievements down. It feels like hope. Mollie Moon was real- her brilliant work was real- and the change and difference she made as one person are still real, still being felt. From a historical perspective, I don’t know what could be more hopeful, or more empowering.

Read more about the Mollie Moon photographs and letter here or contact RBSCP for more information.