November marks the celebration of Native American Heritage month. To honor the occasion, RBSCP will highlight a historical yet conflicting figure in the Native American sphere: Arthur Caswell Parker (1881-1955). As a Seneca Indian himself, he was as an advocate for American Indian Day, which became declared in New York State by May 1916. Over seven decades later, the initial designation of November as National American Indian Heritage Month became approved and has evolved to how we know it today.1

Arthur C. Parker was born on the Cattaraugus Indian Reservation in Erie County, NY in 1881.[1] In fact, Parker was born to a mother of European descent. Parker’s American Indian heritage originates from the paternal side of his family.2 His father, Frederick Ely Parker, held ancestral ties to a prominent Seneca family that eventually settled in the “white world.”3 Traditionally, one would be considered Native American based on their mother’s familial lineage; therefore, Parker himself was not born as an official member of the Seneca Nation of Indians. As a result, Parker migrated between the Christian and Native American realms of his identity throughout his lifetime. His family could not afford the same schooling as his peers, which further isolated him from a European American community.4 For the first eleven years of his life, Parker grew up on a Seneca reservation. In that span of time, many of Parker’s experiences with Native American children and elders who passed on the rich history and folklore of the Seneca Nation would end up shaping his life. In 1903, Parker was honored as an adopted member of the Seneca Nation and given the name Gawasowaneh, which translates to “Big Snow Snake.”5

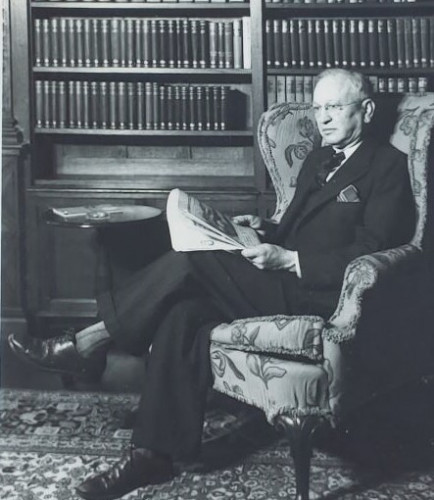

In 1925, Arthur C. Parker became involved in the Rochester Museum of Art and Science as the director, serving for twenty-one years. Preceding this appointment, Parker served as the first archaeologist at the New York State Museum beginning in 1906.6 Parker attended university for a time but felt more compelled to the NYS museum setting. Through a recommendation, he then attended Dickinson Seminary but ultimately did not finish his ministry studies. Throughout this time, he worked on anthropologic projects relating to the Seneca Nation and became a mentee of archaeologist Mark Harrington. Eventually, his dedication led to him becoming an authoritative figure on Seneca Indian culture.7 Parker believed in the importance of sharing Native American knowledge and saw museums as capable of bringing that culture to a wider audience. He guided the assembly of educational dioramas that ultimately led to the development of museum anthropology and curation. What brought these exhibits to life were intricate details; Parker included baskets, paddles, spoons and the like.8 Today the museum, which is located downtown, is known under a slightly different name: the Rochester Museum and Science Center.

Native Americans hold both a rich and tragic history in North America. In Parker’s lifetime, concentrated efforts on the assimilation of Native Americans were prioritized, causing land disputes over Iroquois jurisdiction, for example. Parker prioritized his personal aspiration of receiving eventual recognition as a leader in the anthropology field instead of advocating for Native American rights to remain immersed in their own culture.9 However, a lack of a doctoral degree prevented Parker from receiving proper credit as an anthropologist in the academic sense. His high school education granted him the last of his completed degrees. Furthermore, his studies were limited to museum settings rather than a “university context.”10

In any case, his contributions were vast. RBSCP holds a considerable amount of materials relating to Parker in their collections, where one may find photographs, letters, articles, and speeches. Many of Parker’s publications are available to check out at the River Campus Libraries (RCL); his books about American Indian culture feature a wide range of content from the Seneca Constitution to folk tales. A few highlights in the RCL stacks include: Skunny Wundy: Seneca Indian Tales (1926), Seneca Myths and Folk Tales (1923), Red Jacket, Seneca Chief (1998), The Code of Handsome Lake, the Seneca Prophet (1913), and Iroquois Archeological and Ethnological Papers (1909-1916).

Sources

1 “About National Native American Heritage Month,” The Library of Congress. https://nativeamericanheritagemonth.gov/about.html.

2 Box 5, Folder 3, A.P23, Arthur Caswell Parker papers. Rochester History Vol. XVII July, 1955, No. 3, Edited by Blake McKelvey, City Historians “Arthur Caswell Parker: 1881-1955, Anthropologist, Historian and Museum Pioneer” by W. Stephen Thomas, Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation, River Campus Libraries, University of Rochester.

3 “Ely Parker (1828-1895).” Under the Culture page, Ely Parker is included in a catalog of historical Seneca leaders, Seneca Nation of Indians, https://sni.org/culture/historic-seneca-leaders/.

4 “Parker, Arthur Caswell.” This may be found in the “Considered Non-Indian” section of the article. Encyclopedia of World Biography. Encyclopedia.com. https://www.encyclopedia.com/history/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-....

5 Box 5, Folder 3, A.P23, Arthur Caswell Parker papers, W. Stephan Thomas.

6 Gwendolyn Saul, “Research and Collections of Arthur C. Parker.” Research and collections of Arthur C. Parker. Native American Ethnography. New York State Museum. http://www.nysm.nysed.gov/research-collections/ethnography/collections/r....

7 “Parker, Arthur Caswell.” Encyclopedia of World Biography. This may be found in both the “Considered Non-Indian” and “Honed Writing Skills as Reporter” sections of the article.

8 Saul, “Research and Collections of Arthur C. Parker.”

9 Joy Porter, “Arthur Caswell Parker, 1881-1955: Indian American Museum Professional.” New York History, Vol. 81, No. 2, April 2000, pp. 211-236, https://www.jstor.org/stable/23182336.

10 Porter 220.

[1] Just about a two-hour drive from the University of Rochester.