As one of the most well-known African American poets, Lucille Clifton’s large collection of work spans decades and countless topic. When reading through her works, political undercurrents clearly run through the poems, discussing the issues of race and gender that Clifton herself so often dealt with as a black woman during the civil rights movement.

In February 1968, in Orangeburg, South Carolina, 3 protesters were killed and almost 30 were injured by the Carolina Highway Patrol, at a protest for desegregation of the local bowling alley. In May 1970, police open fired on a group of black students at Jackson State College, killing two and injuring 12.

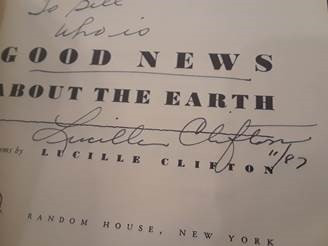

Clifton dedicated her second, and arguably her most political, book Good News About the Earth (1972) to these students, writing:

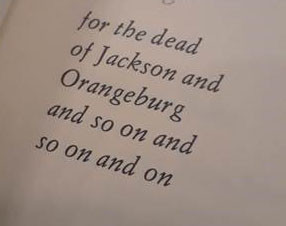

“For the dead

of Jackson and

Orangeburg

and so on and

so on and on”

Clifton's dedication remains especially poignant today.

[Clifton's dedication to the victims of the Jackson and Orangeburg massacres, in "Good News About the Earth"]

This theme of resilience in the face of the brutality and loss in the fight for equal rights is one that continues throughout the rest of the book. “Heroes”, a section in Good News contains poems about figures in the civil rights movement, including Malcolm X.

“nobody mentioned war

but doors were closed

black women shaved their heads

black men rustled in the alleys like leaves

prophets were ambushed as they spoke

and from their holes black eagles flew

screaming through the streets”

In this poem, “Malcolm,” the focus is on the racial tensions that were running so high during the time period, particularly surrounding the assassinations of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr., in 1965 and 1968, respectively (the prophets who were ambushed). The stark imagery present helps conjure images and feelings of the time period, with the fight for rights becoming increasingly more violent, and likewise, more important.

While the bulk of Clifton’s poems focus on this angle of life in the thick of the movement, she also frequently wrote about the unique intersections of both being black and a woman in America. Her poem “apology (to the panthers)” discusses this in particular:

“i became a woman

during the old prayers

among the ones who wore

bleaching cream to bed

and all my lessons stayed

i was obedient

but brothers I thank you

for these mannish days [...]

i had forgotten and

brothers i thank you

i praise you

i grieve my whiteful ways”

One of Clifton’s most famous poems, “homage to my hips,” is about the celebration and acceptance of her body, and it has been accepted as a rallying cry for body positivity and self-love.

“[...] these hips have never been enslaved [...]

these hips are mighty hips.

these hips are magic hips. [...]”

However, in her less well-known poem, Clifton also writes an “homage to my hair,” a poem that focuses on self-love through the lens of her black identity, and the embracing of her hair as another symbol of her beauty.

“when i feel her jump up and dance

i hear the music! My God

i’m talking about my nappy hair! [...]

the grayer she do get, good God,

the blacker she do be!”

Clifton continued to highlight issues of race, class and gender in her children’s books, in addition to tackling tough topics such as death and abuse. However, these books also do the important job of placing black children as the protagonists of the story, an issue we are dealing with in children’s literature today.

Throughout her writings Clifton always made a point to focus on the African American experience and the nuanced political and social issues that come with it, which makes her a perfect author to remember and discuss during Black History Month.

by: RBSCP student employee, Charlotte Stalker '22.