Howard Pyle, The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood of Great Renown in Nottinghamshire. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, MDCCCLXXXIII [1883].

Produced in a larger than usual format – crown octavo – and bound in full leather with elaborate blind-stamped cover (fig. 1), Pyle’s lavish and handsome volume urgently proclaimed to its earliest admirers, this is no ordinary children’s book.

Its publisher, Scribner, was vying for market share in the burgeoning field of children’s literature, and improbably entrusted Howard Pyle (1853-1911) -- a free-lance illustrator and writer who had never produced a book before -- with complete oversight of font, layout, decoration, paper, format, and binding for The Merry Adventures, all this in addition to having him create the story and illustrations (figs. 2-4).

Standard histories credit this volume as exercising “an incalculable influence on the whole course of illustration,” and in particular of establishing a niche for high-end children’s stories that stood apart from the usual run of ephemeral, inexpensive, and flamboyantly colorful publications.

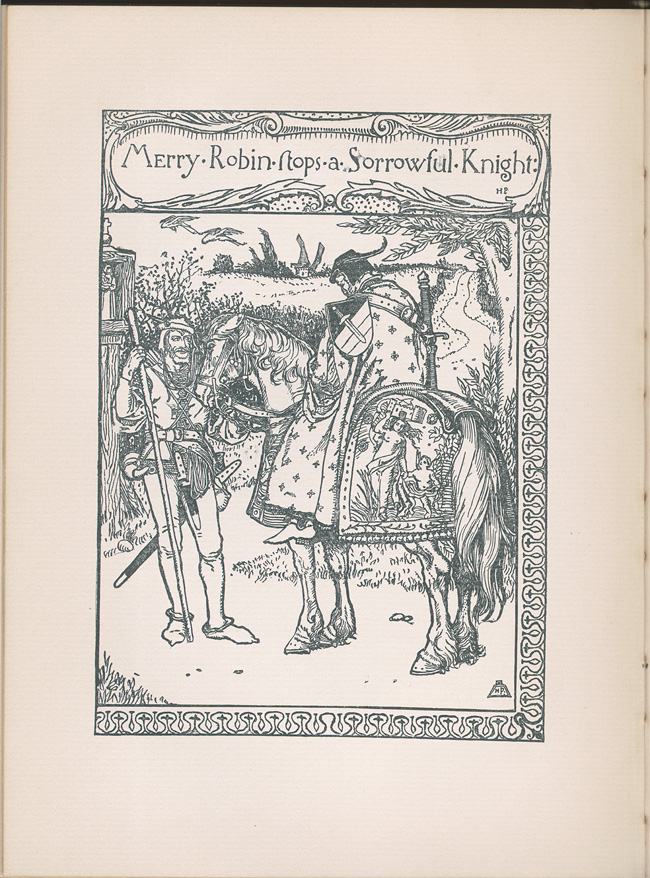

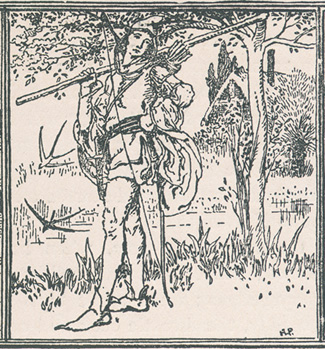

Pyle’s passionate attention to every feature of book design and manufacture marks each page. As illustrator, he not only established the consistent appearance of Robin and his crew as muscled men in tights (fig. 5), but took minute care with borders (adding realistic flora, medievalesque dragon flies, and abstract patterns, fig. 6), historiated initials (fig. 7), rubrication in the front matter (fig. 8), decorations, and vignettes (fig. 9), so that the visual components of the story possess the “reader” as fully as does the text (fig. 10).

Pyle concocted his narrative from a variety of popular sources, beginning with the earliest ballads and tales, but drawing as well on later re-tellings in both verse and prose (fig. 11).

Pyle’s Merry Adventures takes its place between two similarly named landmarks of American literature, Mark Twain’s Adventures of Tom Sawyer (1876) and Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1884). In the former, Twain draws upon his own childhood reading in having Tom and Huck act out episodes (figs. 12-14) from Robin Hood; the illustrations that accompany even a “serious” writer’s version make clear how distinctive and elegant a style Pyle produced for what was professedly a children’s story.

Twain’s fiction insisted that Robin Hood existed not in expensive books but in the mouths and actions of real American children, and in Huckleberry Finn he claimed that the different “dialects have not been done in a haphazard fashion, or by guess-work; but painstakingly, and with the trustworthy guidance and support of personal familiarity with these several patterns of speech.”

Much of Pyle’s success likewise lay in equipping his hero with a new non-local dialect, filled at once with medievalesque archaisms, Quaker locutions from his own family background, and invented constructions straight out of “the land of Fancy” that Robin Hood inhabits.

Having set both a high standard and a high price for the Merry Adventures, Scribner made a firm decision not to dilute the Pyle “brand.” They never issued an inexpensive or paper edition of the volume, and instead carefully controlled its distribution; on average they published every second year a limited run in an attractively printed format that closely imitated the first edition, and in this way insured that Pyle’s book remained relatively scarce and valuable – a keepsake or collector’s book. In 1902 Scribner persuaded Pyle to condense his original, producing Some Merry Adventures so that it could be included in their “School Series,” opening the way for mass purchases for curricular use. Both the narrative and the drawings were reduced in scale. A new edition of Some Merry Adventures was brought out in 1954 in Scribner’s Willow series; its elegant dust jacket maintains the tradition of high-end publication for Pyle. In 1933, for the 50th anniversary of Merry Adventures, Scribner published its Brandywine edition; this included a frontispiece (repeated for the paste-down on the cover) and reminiscence by Pyle’s former student, N. C. Wyeth, who had produced his own rival Robin Hood in 1917. There is also a drawing by Wyeth’s young son, Andrew. Scribner continued its policy of manufactured rarity until their copyright for Merry Adventures expired in 1939. They “revived” Pyle, re-using the plates made for the first edition, in 1946 as part of the celebration of the publisher’s centenary, and then re-set the book completely in their Hudson River Editions series (1988).

Arguably Pyle's illustrations constitute the most distinctive feature of the book. In choosing his models, style, and design, Pyle openly rejected the latest innovations in printing and in children's books, which would have allowed him to incorporate lavish color plates and drawings. Instead, his drawings (like those of William Morris and Edward Burne-Jones for the Kelmscott Press) reflect the work of the earliest engravers and illustrators in the history of the printed book – artists such as Durer, Holbein, and Burckmaier. He even chose to sign and date his drawings in the manner of these first masters of printed illustration.

This results in a simplicity of line and appearance that is at once appropriate to children's books, and historically apt for his chosen subject, the medieval outlaw hero. The distinctiveness and consistency of Pyle’s art makes it seem perfectly fixed, but in fact both the visual and verbal texture of Merry Adventures changed radically over the course of 1883. This alteration is strikingly apparent in the contrast between the two illustrated stories he published in Harper's Young People in January of that year and the mature style of the book published at the end of the year for the Christmas season (figs. 16-17).

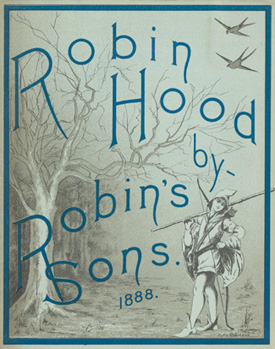

Scribner’s copyright preserved Pyle’s distinctive drawings, with the exception of a few piracies: in 1894 F. Lübcke and J. F. Daugaard published a Danish translation of theMerry Adventures which reproduced the illustrations, coloring them in ways which point up the characteristic beauty and simplicity of Pyle's work, and in 1888 a young Rochester artist, Julia Robinson, copied Pyle’s figure of the young Robin for the cover of her brother’s operetta, Robin Hood: the subject of the Collection Highlight: Robinson. Ye original operetta...Robin Hood.

This blog post was contributed by Thomas Hahn, Professor of English, University of Rochester.