Outreach Librarians Kristen Totleben and Alan Unsworth with Phillip Koyoumjian, instructor for HIS198: Science, Sex and Society in Victorian Britain, approached Liz Call, Outreach Librarian for Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation (RBSCP) about having students engage with rare books to compliment what they were learning in the classroom. The students "speed-dated" with a selection of mostly Victorian-era books that deal with love in some way and selected one that appealed to them. They then were tasked with carefully analyzing their book and writing a brief blog post. Students will share their experiences tomorrow, February 14th, in Evan Lams Square in Rush Rhees Library from 11:30am-1pm (this event is part of a series of events, "Love in the Library," taking place tomorrow).

Madeleine Fordham

Gammer Gurton's garland; or, The nursery Parnassus.

London: Printed for R. Triphook by Harding and Wright, 1810.

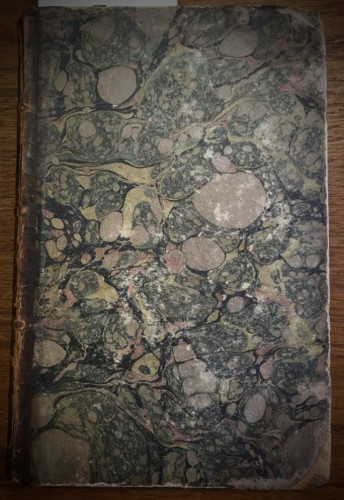

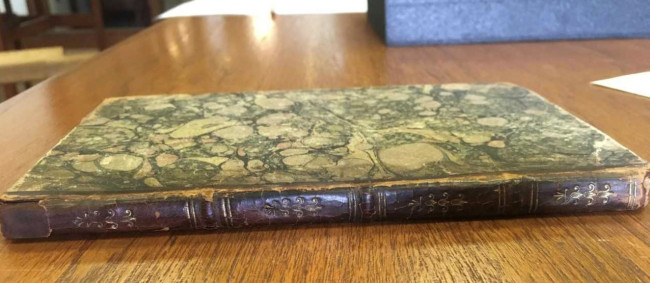

The book’s full title is Gammer Gurton’s Garland or, the Nursery Parnassus: A Choice Collection of Pretty Songs and Verses, for the Amusement of all Little Good Children who can Neither Read nor Run; it was published by Harding and Wright in London in 1810. One can see the chain lines (lines produced by the laying of thinner and thicker wires in the handmould) in the paper, especially in the blank pages that both precede and follow the content. Its cover is marbled in shades of green, yellow, and red, and the spine bears silver decoration. However it is very delicate: the spine shows signs of red rot, a degradation process that occurs in leather.

The contents of the book consist of nursery rhymes of varying length. It contains many pieces still known, like “Bah, Bah, Black Sheep”, “Patty Cake”, “Little Boy Blue”, “Mother Hubbard” and many others (although some lines may not be exactly as we might have learned them). It also contains lesser known poems and songs, like “The Cambrick Shirt”, “A Man of Words” and “Lady’s Song in Leap Year” - a version of which was included in the film Cinderella (2015). Some of the poems are quite sweet, but some are very racy, including lines like, “I’ll come to your wedding/without any bidding/and lye with your bride all night.”

The only real Valentine’s Day related item is the full version of the classic “Roses are red, violets are blue”:

The rose is red, the violet’s blue,

The honey’s sweet, and so are you.

Thou art my love and I am thine;

I drew thee to my Valentine:

The lot was cast and then I drew,

And fortune said it shou’d be you.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Dan Cancelmoa

Lover’s Valentine Writer

By a literary lady

New York: T.W. Strong, 1849.

The small, pocket-sized book, Lover’s Valentine Writer, caught my eye. Upon reading the preface, I was further intrigued. It (I assume, in a tongue-in-cheek manner) condemned those who could find no love “to Lucifer,” stating that he was the patron saint of such matters. I then skimmed through the poems and one-liners and I enjoyed a lot of them. As mentioned, the book is tiny; it is just small enough to fit in one’s pocket. There is no cover or bindings of any sense save a single bit of string running through the pages and tied into a small knot on the back to keep the pages together. The edges are bent showing usage—likely from being placed in one’s pocket—and has old, stained pages.

Back to the actual content of the book it is full of one-liners and short poems ranging from two lines to half of the small pages. The entries are romantic and love poems by a wide array of writers ranging from antiquity to Shakespearean to writers contemporary to Victorians. They are also categorised into situations in which each one might be appropriate or particularly effective such as: “With a rose” and “to the betrothed”..This book would be read by ladies seeking and hoping for romance as well as gentleman looking for things to say in order to woo the aforementioned ladies. This compilation of other’s works was compiled by an anonymous “Literary Lady” and published in New York City. In the Victorian era it would be inappropriate for a woman, especially a well-born lady, to publish a book and so it is anonymous.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________

Jina Lee

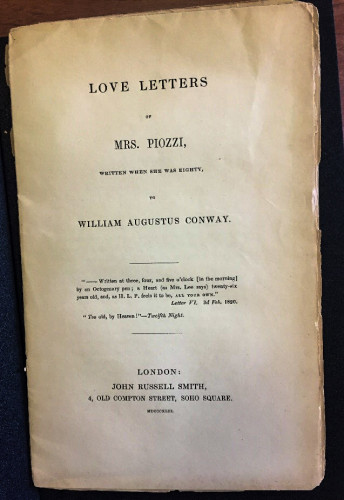

Love Letters of Mrs. Piozzi: written when she was eighty, to William Augustus Conway

London: John Russell Smith, 1843.

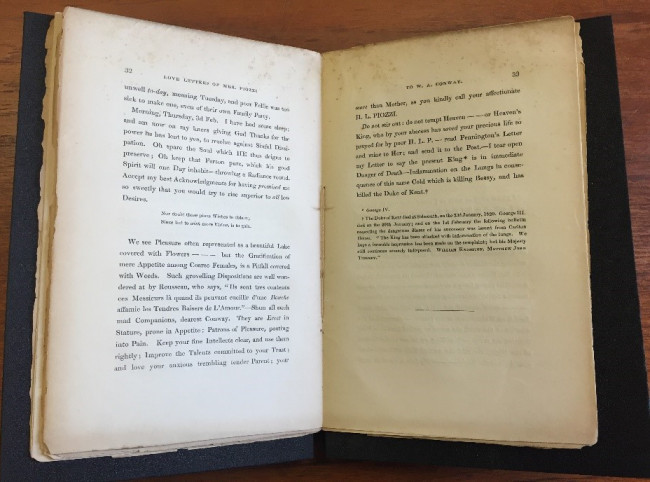

What first attracted me to Love Letters of Mrs. Piozzi: Written When She Was Eighty to William A. Conway was the fragile state in which the book was. Compared to hardbound books with sewn binding, this small pamphlet-like book was printed on aged paper all bound together with a single thread in the middle of the pages, which made the experience of reading work from the Victorian Era authentic. I initially had difficulty even reading the letters as they were in the form of an uncut book, meaning that the top of each page was adjoined to the following page, requiring a penknife to separate them. In addition, the size of the pages was bigger than that of a traditional book during the Victorian Era, with big, clear fonts, making the letters easy to read. I was surprised that the letters had been published; I wondered why anyone would publish love letters filled with one’s highly personal feelings and thoughts to be read by the general public. I was also curious who Mrs. Piozzi and Mr. Conway were as the love story of the couple. Therefore, I proceeded to investigate their life stories.

Mrs. Piozzi, born Hester Lynch Salusbury in 1741 to an affluent Welsh land-owning aristocratic family, lived the life of an aristocrat, receiving a classical education in Greek and Latin until her father went bankrupt, prompting her marriage to the rich brewer Henry Thrale, Esq., of Southwark. Her husband’s enormous wealth allowed her to become acquainted with men of wit and education and be at liberty to write entertaining letters to her friends of the latest gossip in her community. She also wrote several memoirs and even her own account of historical events in the last eighteen hundred years during her first marriage. However, Mr. Thrale died in 1780. Whereas she had married her first husband out of financial necessity, she decided to marry her second husband, Gabriel Mario Piozzi, out of true love. Even though she was criticized by her own family and her aristocratic group of friends for desiring to marry Mr. Piozzi as a woman of her wealth and nobility should not marry a man of poor wealth and even worse, a foreigner who was Roman Catholic, she married him when she was 44. She formed a new, artistic circle of friends after her old circle had abandoned her. However, she was again left a widow in 1809 when Mr. Piozzi died.

Sadly, Mrs. Piozzi never seems to have found true love after Mr. Piozzi. Many believe that when Mrs. Piozzi was eighty years old, she fell in love with William Augustus Conway, a handsome, tall, 23-year-old actor. This belief was due mainly due to the prologue to the love letters that she had supposedly written to Mr. Conway. According to the prologue, Mrs. Piozzi, once again, was willing to pursue a man of her desires despite him being much younger than herself. She wrote a total of seven letters to Mr. Conway for two years until her death at 82 years of age although it is unknown as to whether he ever replied to Mrs. Piozzi, hinting of this love being one-sided. Advertising the letters as love letters made for a salacious story; however, after having read her letters myself, Mrs. Piozzi sounds more like Mr. Conway’s fan: she expresses concern for his “ill health from Fortune and from Fame” and, promising to pray for him, encourages him to never give up hope despite all the difficulties associated with succeeding as an actor. Her relationship to Mr. Conway seems more like that between a grandmother and a grandson, devoted and affectionate but not of true love. According to The True Story of the So-Called Love Letters of Mrs. Piozzi by Percival Merritt, much of the punctuation and content of the original letters had been unfaithfully copied in the published copy as to distort their meaning. Although not explicitly stated in the letters, Mrs. Piozzi was aware of Mr. Conway’s long unsuccessful love affair with Miss Stratton, referring to Miss Stratton as the “China Rose, of no good scent or flavor,” comforting Mr. Conway even after the relationship had ended.

After Mr. Conway committed suicide in 1828, his relatives sold his belongings; among them were the letters from Mrs. Piozzi. They were bought by a lady named Ellet, who lent them to a gentleman who published in London them 1843. However, according to historical records, Mrs. Ellet was ten to eleven years old at the time when she had supposedly bought the letters; hence, the circumstances under which the letters were obtained for publication are suspicious. She did come into possession of them later on in her life, but it is unclear as to when exactly the letters were taken from Mr. Conway’s possession. In knowing the true story behind Mrs. Piozzi’s letters, I wonder why the unnamed editor of the prologue would risk potentially harming Mrs. Piozzi’s reputation in falsely stating that she was in love with a man much younger than herself? Whose decision was it to publish Mrs. Piozzi’s letters without her family’s permission? One things is for sure: there is much more mystery surrounding Mrs. Piozzi’s letters than meets the eye.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________

Sarah Elbert

The Love Letters of Mary, Queen of Scots, to James, Earl of Bothwell; with her love sonnets and marriage contracts...

London [1824]

One of the gems housed in the University’s Rare Books Library is a copy of The Love Letters of Mary Queen of Scots. The copy housed here once belonged to prominent English writer and critic William Rossetti, brother of Dante Gabriel and Christina Rossetti, whose own annotations and opinions can be found within the text.

From outward appearances alone, the book appears old and elegant; of another time. Gold stamping that appears to be some sort of emblem or crest makes up the binding, intricate blue endpapers line the covers, and the pages are thick, rough, and yellowed with age. The book itself contains love letters written from Mary Queen of Scots to her lover, the Earl of Bothwell. She proclaims her desire for him, although social constraints prevent them from being together: he is married, and she must marry someone of higher status to retain her position as Queen. “Letter the Fourth” describes to him this predicament; she has just married another man, Lord Darnley, and condemns the Earl for his anger at her marriage. She explains that taking him as a husband was necessary; the only way to end her deprivation of “everything but the name of queen.” In later letters it is shown that she and the Earl continue to meet with one another in secret, as her marriage becomes increasingly miserable. Things escalate further as the letters progress, as she describes the murder of her husband and the Earl’s upcoming divorce from his wife, of course without placing any blame or connection between the events that are arguably orchestrated by the pair to allow for their own marriage.

In a modern society where the choice of who to marry is associated with love alone, it is shocking for us readers to see a marriage that is merely a facade, where a wife is forced to seek romance elsewhere. Equally shocking are the drastic measures taken to leave this marriage; the fact that murder and getting a Bishop’s dispensation to leave ones wife are the only way for two lovers to be together. This book shows us the human side of this historical figure, as she seeks her own fate against a strong social hierarchy, and with tragic consequence.

By: Liz Call, Outreach Librarian for Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation